The neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is a site of medical treatment for premature and critically ill infants. It is a space populated by medical teams and their patients, as well as parents and family. Each actor in this space negotiates providing and practicing care. In this paper, we step away from thinking about the NICU as only a space of medical care, instead, taking an anti-essentialist view, re-read care as multiple, while also troubling the community of care that undergirds it. Through an examination of the practice of kangaroo care (skin-to-skin holding), human milk production and feeding, as well as, practices related to contact/touch, we offer a portrait of the performance of the community of care in the space of the NICU.

Articles

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated response have brought food security into sharp focus for many New Zealanders. The requirement to “shelter in place” for eight weeks nationwide, with only “essential services” operating, affected all parts of the New Zealand food system. The nationwide full lockdown highlighted existing inequities and created new challenges to food access, availability, affordability, distribution, transportation, and waste management. While Aotearoa New Zealand is a food producer, there remains uncertainty surrounding the future of local food systems, particularly as the long-term effects of the pandemic emerge.

Until recently, bottled drinking water was a cause of concern for development in the Global South; now, however, it is embraced as a way to reach the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goal target 6.1 for "[u]niversal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all". Reaching SDG 6.1 through bottled drinking water is controversial as there are broad questions about how any form of packaged – and therefore commodified – water can be ethical or consistent with "the human right to water" that was ratified in 2010 by the United Nations member states. By examining a social innovation enacted by a Cambodian NGO, this research questions polarising narratives of marketised and packaged water.

J.K. Gibson-Graham’s postcapitalist approach to diverse economies has unleashed a flourishing of research and activism for other worlds. One reason for its successes is found in the intricate links between a feminist and antiessentialist critique of political economy and an experimental, enabling, and affirmative practice of economy. While initially powered by explicitly critical and negating energies, diverse-economies scholars have increasingly accentuated an affirmative, “post/critical” register. This essay explores what has happened to “capitalocentrism” in this process.

Sustainability has emerged as a central concept for discussing the current state of the human-environment system and planning for its future. To delve into the depths of sustainability means to talk about ecology, economy, and equity as fundamentally interconnected. However, each continues to be colonized by normative epistemologies of ecological sciences, neoclassical economics, and development, suggesting that with enough science and development, a more equitable sustainability is achievable. In our analysis, place emerges as an alternative epistemology through which to analyze sustainability.

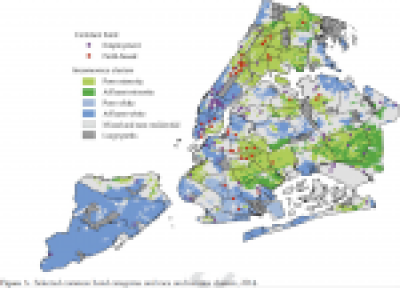

About 6,000 financial cooperatives, called credit unions, with more than 103 million members manage over $1 trillion in collective assets in the United States but are largely invisible and seen as inferior to private banks. In contrast to banks that generate profit for outside investors and do not give voice to customers, these not-for-profit institutions have a democratic governance structure and a mission to provide good services to their members. We use diverse economies and critical/feminist GIS approaches to theorize them as noncapitalist alternatives to banks and possible sites of social transformation toward a solidarity economy.

In this expansive conversation, we explore the current political-cultural conjuncture in the United States. Thinking through the responses to the pandemic and the Floyd Rebellion, Akuno analyzes the violence of and tensions between an escalating white supremacy, on one hand, and an intractable (neo)liberalism that is attempting to capture and channel the energies and ideas of the Left, on the other. Akuno locates direction for the Left amid the flourishing of mutual-aid projects and the possibility of a politicized solidarity-economy movement that can fight for and build practices, relationships, and institutions beyond the limitations of the market, the state, and what is deemed to be practical.

In this paper I explore the possibility of the feminist ethic of care to enhance urban theory by placing emphasis upon our collective interdependence and responsibility to one another. As an ethics, care has the potential to maintain, continue, repair and transform our worlds. As a practice, care is often hidden from view despite the integral role care plays in ensuring survival in our worlds of both human and non-human others. As a performative act attuned to the possibility of care in the city I discuss how care was manifest in this space of care by drawing on research undertaken at The Women’s Library, Newtown which is located in Sydney, Australia. I reflect upon care-full practices that maintain, continue and repair our worlds within and beyond the library.

In this paper we present a method for valuing the multidimensional aspects of urban commons. This method draws from and contributes to a broader conception of social or community returns on investment, using the case and data of a vibrant project, strategy, and model of ecological resilience, R-Urban, on the outskirts of Paris. R-Urban is based on networks of urban commons and collective hubs supporting civic resilience practices. We use data from 2015, the year before one of the hubs was evicted from its site by a municipal administration that could not see the value of an ‘urban farm’ compared to a parking lot.

This paper is based on the 2016 Neil Smith lecture presented at St Andrews University. It honours the work of a geographer whose pioneering work on uneven development and the complex relations between capitalism and nature shaped late 20th century thinking inside and beyond the discipline of Geography. Today the collision of earth system dynamics with socio-economic dynamics is shaking apart Enlightenment knowledge systems, forcing questions of what it means to be a responsible inhabitant on planet earth and how, indeed, to go onwards ‘in a different mode of humanity’ (to quote eco-feminist philosopher Val Plumwood).

This paper contributes an intersectional feminist analysis and methodological approach to debates about commoning and social enterprise. Through a narrative description of feminist social enterprise projects based on action research with the Kinning Park Complex, a social centre with a radical history in Glasgow’s South Side, I demonstrate how contemporary community economic development models can entrench intersectional exclusion. Specifically, I show how market‐oriented social enterprise models reproduce precarious work, hinder cooperative ethics, and promote depoliticised notions of difference. However, I also investigate the ways that community organisers and activists at KPC are re‐working these neoliberal models to carve out spaces for feminist commoning.

In this essay I reflect on and theorize efforts to teach, learn, and advance solidarity economy, a movement and design project to create the conditions for community determination and collective well-being. I draw from five years of ethnographic work and two years of teaching efforts to reassemble the resources at hand into a pedagogical intervention along the lines of what Jon Law (2004) describes as a “methods assemblage,” a set of practices, techniques, and relations that work to organize and condense particular realities. I explore how a methods assemblage of solidarity economy can open epistemological, ideological, and material trajectories toward other ways of being in the world.

In this article, Katharine and Kelly reflect on the role of the body in ethnographic research, suggesting some questions we might consider as we seek to create caring academic communities supporting each other in ethnographic work.

In Transcending Capitalism Through Cooperative Practices, Mulder shows how exploitation, and non-exploitation, can be analytically discerned, and she describes some various contexts in which non-exploitation exists. Mulder's analysis, analytical approach, and contextual descriptions, surface and prompt important questions around the conditions of possibility for imagining and actualizing economic difference and transformation. To help elaborate and begin to address these questions, I turn to a growing movement in Massachusetts in which communities are crafting and organizing around their own conditions of possibility in innovative and powerful ways.

In this article I analyse beekeeping expertise as situated knowing in the precarious conditions of multispecies livelihoods. Beekeeping is knowledge-intensive: distinct expertise is required to keep colonies alive and thriving, to produce honey, and to support pollination – that is, to maintain livelihoods. The conditions in which beekeeping expertise is developed and enacted are precarious due to close entanglements with ultimately unintelligible non-human others and their changing habitats. Using ethnographic and interview data collected among urban beekeepers in Finland, I first describe the precariousness embedded in beekeeping as sharing lifeworlds and becoming with non-human others, particularly in an epoch characterized by severe environmental disturbances.

Planning for climate change is complex. There is some uncertainty about how quickly the climate will change and what the anticipated localised effects will be. There are also governance questions, for instance, who has the mandate to make decisions around the management of collective resources (like council infrastructure) and private property. Underlying these questions are issues of justice, equity and agency – who pays for the costs of adaptation and mitigation, and how do decision-makers engage with communities when what is ultimately needed is transformational socio-economic change?

Avec d’autres chercheuses et chercheurs engagés, je lutte pour rompre avec une conception universaliste du monde et opérer une transition vers un vivre-ensemble « centré sur le plurivers constitué d’une multiplicité de mondes enchevêtrés et co-constitutifs, mais distincts ». Dans le sillon de Dardot et Laval3, je comprends la révolution comme un moment d’accélération, d’intensification et de collectivisation d’une activité autonome et auto-organisée dans toutes les sphères de la vie économique, sociale, politique ou culturelle. Avec eux, je crois que le principe du commun est au coeur de ce projet révolutionnaire…

It appears that an almost unquestioned development pathway for achieving gender equity and women’s empowerment has taken centre stage in mainstream development. This pathway focuses on economic outcomes that are assumed to be achieved by increasing women’s access to material things, including cash income, loans, physical assets, and to markets. Gender equity indicators, which measure progress toward these outcomes, cannot escape reinforcing them. We argue that far from being neutral; indicators are embedded in political and ideological agendas that serve as guides to the appropriate conduct of those whose performance or behaviour is being measured.

Policy proposals about social change and well-being shape the implementation of applied theatre projects through technologies such as evaluation practices and funding applications. Representations of projects can, in turn, effect public discourse about who participants are and why they are or are not ‘being well’. Like public policy, applied theatre for social change has to establish a problem that needs to be solved. Drawing on debates about change in applied theatre literature, we consider how funders, governments, and communities call on applied theatre practitioners to frame particular issues and/or people as problematic.

This paper examines the geography of local food through a spatial analysis of farms and farmers’ markets. It draws on two themes in the geo-graphical literature on local food, which focus on territorial and prox-imity definitions on one hand and on relationality on the other. Through GIS analysis, this paper explores spatial patterns of ninety-one farmers’ markets in Los Angeles County, California, USA; spatial patterns of 282 farms that supplied a sample of thirty-three markets; and intra-urban patterns of those supply chains. The results show an uneven geography of farms across California that supplied the sampled markets, but also show that farms travel just as far to markets in working-class neighborhoods as to wealthier neighborhoods.

This paper discusses the Inpaeng Network, an alternative farmers' organization in Northeastern Thailand, and its cooperative ventures with state institutions. The primary aim is to show how by drawing on state development discourse participants in community economies can make use of government assistance and resources for their projects.

We use two Christchurch case studies to think about the temporality of commoning, concluding that even transitional and temporary commoning can help normalise and make visible the practice, thus enabling commoner subjectivities.

What does it mean to be at home in a hot city? One response is to shut our doors

and close ourselves in a cocoon of air-conditioned thermal comfort. As the climate

warms, indoor environments facilitated by technical infrastructures of cooling are

fast becoming the condition around which urban life is shaped. The price we pay for

this response is high: our bodies have become sedentary, patterns of consumption

individualized, and spaces of comfortable mobility and sociality in the city, termed

in this paper as “infrastructures of care,” have declined. Drawing on the findings

of a transdisciplinary pilot study titled Cooling the Commons, this paper proposes

that the production of the home as an enclosed and private space needs to be

This article addresses the current restructuring of academia in Turkey through the example of the Academics for Peace petition and the institutional mechanisms of repression it instigated. We focus on the Solidarity Academies as alternative spaces of education and a unique form of collective resistance against the academic purges. We provide an empirically informed analysis of Solidarity Academies as spaces of commoning, the collective production and sharing of knowledge by emergent communities of struggle.

We are thrilled by Vicky Lawson’s deeply appreciative response to the Roepke Lecture and the written article. In her response, Vicky does more than we could ask for by inviting economic geographers to think with us about ways of reworking manufacturing (and other economic activities) that center on care for the well-being of people and of the planet. Vicky goes to the heart of our project by highlighting the importance we place on looking for the ethical openings that arise in the current context of climate change and growing socioeconomic inequality. As she identifies, part of our armory includes tactics of attending to already existing possibilities that are hidden from view and reframing understandings of what an economy is for.

In a world beset by the problems of climate change and growing socioeconomic inequality, industrial manufacturing has been implicated as a key driver. In this article we take seriously Roepke’s call for geographic research to intervene in obvious problems and ask can manufacturing contribute to different pathways forward? We reflect on how studies have shifted from positioning manufacturing as a matter of fact (with an emphasis on exposing the exploitative operations of capitalist industrial restructuring) to a matter of concern (especially in advanced economies experiencing the apparent loss of manufacturing). Our intervention is to position manufacturing for the Anthropocene as a matter of care.

This note explores examples of co-operative ways of organizing work and life that are rooted in a desire for radical eco-social change. We look at and unravel the politics of work and the ecology of support of Footprint, a worker-owned printing co-operative, which is located in Leeds (UK). The first part places special attention on the values and value-practices that inform the co-op’s daily activities, while the second part explores how the sustainability of Footprint’s radical working methods are interlinked with their participation in a (trans)local ecology of social and environmental activism.

In 2012, I was involved in the experimental study program, Campus in Camps, which is located in the West Bank and which brought together 15 third-generation refugees to study the contemporary condition of Palestinian refugee camps and to speculate about their potential futures. In this article, I draw on my experience at Campus in Camps in order to reflect on how design and speculation can be activated by designers and non-designers to speculate with care about the matters of their own lives. To explore the potential held by the design speculations produced at Campus in Camps, I draw on the work of feminist philosopher Marìa Puig de la Bellacasa around " matters of care ".

This article draws from and advances urban studies literature on ‘creative city’ policies by exploring the contradictory role of queer arts practice in contemporary placemarketing strategies. Here I reflect on the fraught politics surrounding Radiodress’s each hand as they are called project, a deeply personal exploration of radical Jewish history programmed within Luminato, a Toronto-based international festival of creativity. Specifically, I explore how Luminato and the Koffler Centre, a Jewish organisation promoting contemporary art, regulated Radiodress’s work in order to stage marketable notions of ethnic and queer diversity. I also examine how and why the Koffler Centre eventually blacklisted Radiodress and her project.

This contribution calls attention to the values of assemblage thinking for the study of contentious economies. A syntactical perspective can make visible social arrangements that are otherwise difficult to represent in traditional social movement categories. With the help of a jar of jam, an object that has meaningful entanglements in anti-camorra activism in Campania (Italy), the article begins by empirically illustrating instances of mobilisation that disrupt relationships of mafia dependency. The focus lies on the force of composition, the syntax of contention. The second section moves on to explore the theoretical backdrop of the analysis, and does so by suggesting some possible points of dialogue between social movement studies and assemblage thinking.