Publications

A short collection of tricks, loops, swerves and contemplation on the administrative, edited by Kate Rich and Angela Piccini.

Fair trade certified exchanges are often cast as an ethical purchasing choice compared to those conducted as part of free trade. Producers are cast as members of marginalized communities who can ‘lift themselves out of poverty’ by producing for the certified market. Third-party certifiers claim that consumers can empower producers, reduce poverty, and improve communities through their purchases. Here, fair trade exchanges may be read as a site of ethical encounter. In this chapter I argue that despite attempts to cast fair trade as an ethical encounter, these claims are mired in a capitalocentric worldview that puts profit ahead of people.

The neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is a site of medical treatment for premature and critically ill infants. It is a space populated by medical teams and their patients, as well as parents and family. Each actor in this space negotiates providing and practicing care. In this paper, we step away from thinking about the NICU as only a space of medical care, instead, taking an anti-essentialist view, re-read care as multiple, while also troubling the community of care that undergirds it. Through an examination of the practice of kangaroo care (skin-to-skin holding), human milk production and feeding, as well as, practices related to contact/touch, we offer a portrait of the performance of the community of care in the space of the NICU.

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated response have brought food security into sharp focus for many New Zealanders. The requirement to “shelter in place” for eight weeks nationwide, with only “essential services” operating, affected all parts of the New Zealand food system. The nationwide full lockdown highlighted existing inequities and created new challenges to food access, availability, affordability, distribution, transportation, and waste management. While Aotearoa New Zealand is a food producer, there remains uncertainty surrounding the future of local food systems, particularly as the long-term effects of the pandemic emerge.

This chapter looks at social enterprise through a lens inspired by community economies and post-development. Without refuting that any trading enterprise must take form in one way or another, the authors look beyond essentialist models towards the embodiment of ‘social enterprising’; a term capturing various processes and intuitions that enact the social through bold economic experiments and that help multispecies communities to live well together. ‘Decolonial love’ and Buddhist teachings of ‘loving kindness’ (Mettā) are mobilized as a way of framing context in Eastern Cambodia and a University Town in Central Canada.

In answering the following research question: What design features allow for both comfort and mobility in the hot city, and what design features detract from this? What climate-resilient social practices are these features enabling and disabling? this report develops a new approach to understanding and designing cool cities: cool commons. The report sets out the new conceptual approach of Cool Commons. It moves beyond current technocentric approaches to cool urban futures, recognising that a combination of material, social and institutional strategies are required to support climate adaptation, including community-led adaptive practices. ‘Cool commons’ view the city not as a collection of private spaces, but as an environment for convivial social life.

During a three-day gathering in the Italian Alps in 2019, we wanted to explore how practices of community economies are being activated by people coming from an art and design background in a variety of local contexts. This practice exchange was an occasion to bring together practitioners and theorists to work together on concrete case studies of artist and designers activating community economies in diverse places across Europe. Another objective was to support several local projects in developing or strengthening their community economies approach.

Until recently, bottled drinking water was a cause of concern for development in the Global South; now, however, it is embraced as a way to reach the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goal target 6.1 for "[u]niversal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all". Reaching SDG 6.1 through bottled drinking water is controversial as there are broad questions about how any form of packaged – and therefore commodified – water can be ethical or consistent with "the human right to water" that was ratified in 2010 by the United Nations member states. By examining a social innovation enacted by a Cambodian NGO, this research questions polarising narratives of marketised and packaged water.

In this chapter, Joanne and Kelly discuss partnerships between Indigenous methodologies, such as Kaupapa Māori research, and community economies research.

In this chapter, Kelly lays out the case for proliferating and valuing caring labour, so that all kinds of different people might share in it.

J.K. Gibson-Graham’s postcapitalist approach to diverse economies has unleashed a flourishing of research and activism for other worlds. One reason for its successes is found in the intricate links between a feminist and antiessentialist critique of political economy and an experimental, enabling, and affirmative practice of economy. While initially powered by explicitly critical and negating energies, diverse-economies scholars have increasingly accentuated an affirmative, “post/critical” register. This essay explores what has happened to “capitalocentrism” in this process.

Humans depend on fungi to provide food and medicine, and to maintain the environments we inhabit. Yet their conservation has not captured the attention of conservationists, perhaps because existing normative economic, ecological, and social ways of creating value for plants and animals are a challenge to adapt for fungi. Using a critical physical geography perspective, this chapter argues that the value of fungi becomes clearer using alternative forms of accounting focused on interconnectivity. The concept of econo-ecologies refocuses value on the importance of work and exchange. For fungi, econo-ecological conservation is generated through sustainable livelihood practices, and ethical biogeographies.

This chapter in the Handbook of Environmental Sociology is based on a particular understanding of post-capitalism, as a series of strategies for socio-economic-ecological negotiations. These strategies engage 1) the politics of language, 2) the politics of the subject, and 3) the politics of collective action. Understanding language, subjects, and collective actions as spaces for political engagement is about considering them as processes actively and always under negotiation rather than as fixed objects. Using these strategies I consider the question: what does sustainability look like in a post-capitalist world? Specifically, how can a post-capitalist politics support and enrich the concept of emplaced sustainability?

Environments and ecosystems around the world support human life, culture and basic needs in myriad ways. Indeed, the ‘labour’ of non-humans, or Earth Others, as we refer to them here, is hugely diverse. But ecological descriptions of Earth Other interdependencies demonstrate that rethinking labour to build sustainable futures should not be a purely human-focused project. Much of the work that keeps our planet going has nothing to do with humans. We humans benefit from it but it is not for us. Today a growing dissatisfaction with an exclusive focus on human livelihoods at the expense of planetary livelihood has created a demand to attend to non-human labour and the work it does. In this chapter we explore the work Earth Others do. What does it look like?

Sustainability has emerged as a central concept for discussing the current state of the human-environment system and planning for its future. To delve into the depths of sustainability means to talk about ecology, economy, and equity as fundamentally interconnected. However, each continues to be colonized by normative epistemologies of ecological sciences, neoclassical economics, and development, suggesting that with enough science and development, a more equitable sustainability is achievable. In our analysis, place emerges as an alternative epistemology through which to analyze sustainability.

I explore three sites that I was involved in commoning in a post-industrial working class neighbourhood in Montreal: a garden on a city-owned plot of land, a mural on a stock-corporation-owned viaduct and a community-owned industrial building “expropriated” from a capitalist developer after a 10-year grassroots campaign. In each of these sites new property relations were forged, ones where a commoning-community manages the space and benefits from how the space has been shaped. Each community is engaged in a continuous process of making and re-making as it is confronted with powerful forces that seek to enclose or uncommon the property it has taken responsibility for.

Voici deux entrevues qui donnent à voir le portrait et le parcours de deux femmes anarchistes, l’une en France, l’autre au Québec.

Irène Pereira et Anna Kruzynski, qui ne se connaissent pas, tiennent des propos qui se font écho, en particulier quant à leur manière de mobiliser prudemment l’étiquette d’« anarchaféministe », même si elles ont plusieurs expériences dans des collectifs féministes. Aujourd’hui, elles s’intéressent et se préoccupent de toutes les formes de domination et cherchent à intégrer dans leur anarchisme des réflexions et des expériences d’ailleurs, par exemple des mouvements afro-américains, autochtones et latino-américains.

Icebergian Economies of Contemporary Art offers reflections on art and economy, stimulated by J.K. Gibson-Graham’s representation of the economy as an iceberg. Themes include visible/invisible; blue line or the surface; the gloss over the dark matter; me versus the many; and art world/s.

An online version of the book is available here. The book was a contribution to a larger project, Cyber-PiraMMMida, which explores the pyramidal spectres and structures which haunt the worlds of architecture, art, academia and the everyday.

Collectively performed reciprocal labour involves a non-monetized exchange of group work done by community members for the benefit usually of one community member or household. In this chapter I shed light on the ubiquity of collectively performed reciprocal labour exchange, thereby establishing its legitimacy in a diverse economy.

This chapter in the Methodology Part VI of The Handbook of Diverse Economies discusses reading as a practice of knowledge production. It introduces 'critical reading' as a reading for dominance and lays out techniques of deconstruction and queering to show what reading for difference might entail.

Economic diversity abounds in a more-than-capitalist world, from worker-recuperated cooperatives and anti-mafia social enterprises to caring labour and the work of Earth Others; from fair trade and social procurement to community land trusts, free universities and Islamic finance. The Handbook of Diverse Economies presents research that inventories economic difference as a prelude to building ethical ways of living on our dangerously degraded planet.

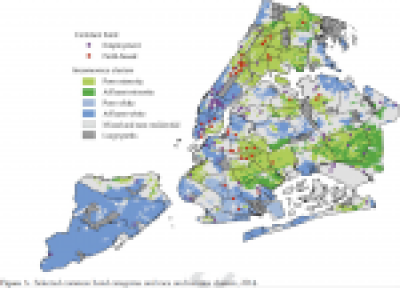

About 6,000 financial cooperatives, called credit unions, with more than 103 million members manage over $1 trillion in collective assets in the United States but are largely invisible and seen as inferior to private banks. In contrast to banks that generate profit for outside investors and do not give voice to customers, these not-for-profit institutions have a democratic governance structure and a mission to provide good services to their members. We use diverse economies and critical/feminist GIS approaches to theorize them as noncapitalist alternatives to banks and possible sites of social transformation toward a solidarity economy.

In this expansive conversation, we explore the current political-cultural conjuncture in the United States. Thinking through the responses to the pandemic and the Floyd Rebellion, Akuno analyzes the violence of and tensions between an escalating white supremacy, on one hand, and an intractable (neo)liberalism that is attempting to capture and channel the energies and ideas of the Left, on the other. Akuno locates direction for the Left amid the flourishing of mutual-aid projects and the possibility of a politicized solidarity-economy movement that can fight for and build practices, relationships, and institutions beyond the limitations of the market, the state, and what is deemed to be practical.

In higher education, efforts to diversify the workforce and create a more inclusive and repre- sentative environment for students and employees have often been stymied by institutionalized racism, a lack of resources, and a lack of institutional energy. In this chapter I discuss an action research intervention, inspired by diverse economies scholarship, that was aimed at valuing and strengthening diversity and inclusion in a community college setting. A starting point for the project was the recognition that within the workplace there are multiple forms of work being performed, and associated ways of being, that fall outside of the traditional identity of a waged worker being paid for services rendered.

In this paper I explore the possibility of the feminist ethic of care to enhance urban theory by placing emphasis upon our collective interdependence and responsibility to one another. As an ethics, care has the potential to maintain, continue, repair and transform our worlds. As a practice, care is often hidden from view despite the integral role care plays in ensuring survival in our worlds of both human and non-human others. As a performative act attuned to the possibility of care in the city I discuss how care was manifest in this space of care by drawing on research undertaken at The Women’s Library, Newtown which is located in Sydney, Australia. I reflect upon care-full practices that maintain, continue and repair our worlds within and beyond the library.

After five years of the consolidation, Mutual Support-Rekülüwun can be seen as part of a repertoire of creative responses by Mapuche families to the monetization of their rural economies in southern Chile, which has accelerated notoriously in the last decade. The project was set out in 2012 by the Mapuche-Lafkenche community of Llaguepulli and MAPLE, to create a member-owned institution while abiding to an indigenous cultural context and community protocols.